FLORIDA SETTLES WITH CIRCLE K OUT OF COURT IN TRADEMARK PLANNING CASE

For those people in the state and local tax profession, trademark planning strategies for reducing corporate state income tax liabilities is nothing new. However, you will be glad to know that trademark planning is still alive and well to assist profitable companies in reducing their 5% Florida corporate income tax liabilities. We can say this confidently because the Florida Department of Revenue and the attorney general's office have backed down in yet another attempt to stop the corporate tax reducing strategy by settling the Circle K case.

For those people in the state and local tax profession, trademark planning strategies for reducing corporate state income tax liabilities is nothing new. However, you will be glad to know that trademark planning is still alive and well to assist profitable companies in reducing their 5% Florida corporate income tax liabilities. We can say this confidently because the Florida Department of Revenue and the attorney general's office have backed down in yet another attempt to stop the corporate tax reducing strategy by settling the Circle K case.

For those of you that are not old school state and local tax professionals, I'll give you a quick lesson in the trademark planning strategy (which has been around since the early 80's). Let's say that you own a company with a very well known name brand, such Toys R Us. Everyone that drives by your stores knows exactly who your company is, what you sell, and if they want to be children's toys, then your store is the place to go. The Toys R Us name brand is very valuable ... as in hundreds of millions of dollars valuable. The problem is - you may have spent a very small amount of money creating this piece of intellectual property, but you can only amortize (deduct) the cost of that property, not the fair market value of the property for tax purposes. This doesn't seem exactly fair. Some very smart tax people figured out a way to take a tax advantage of the fair market value of the property, at least at the state income tax level.

Here's the idea they came up with: Move all your valuable intellectual property into a subsidiary located in a state with no corporate income tax. Then, license that intellectual property to all your subsidiaries throughout the country for a royalty fee of say 3% of gross revenue. The subsidiaries located in most states, including Florida, would take a state tax deduction for the royalty fee but the trademark holding company, located in a state like Nevada with no corporate income tax, would not have state taxable income. So if a company had $100 million of gross revenues in Florida, then it would tax a $3 million state income tax deduction for the royalty fee, saving approximately $150,000 a year in Florida corporate income taxes.

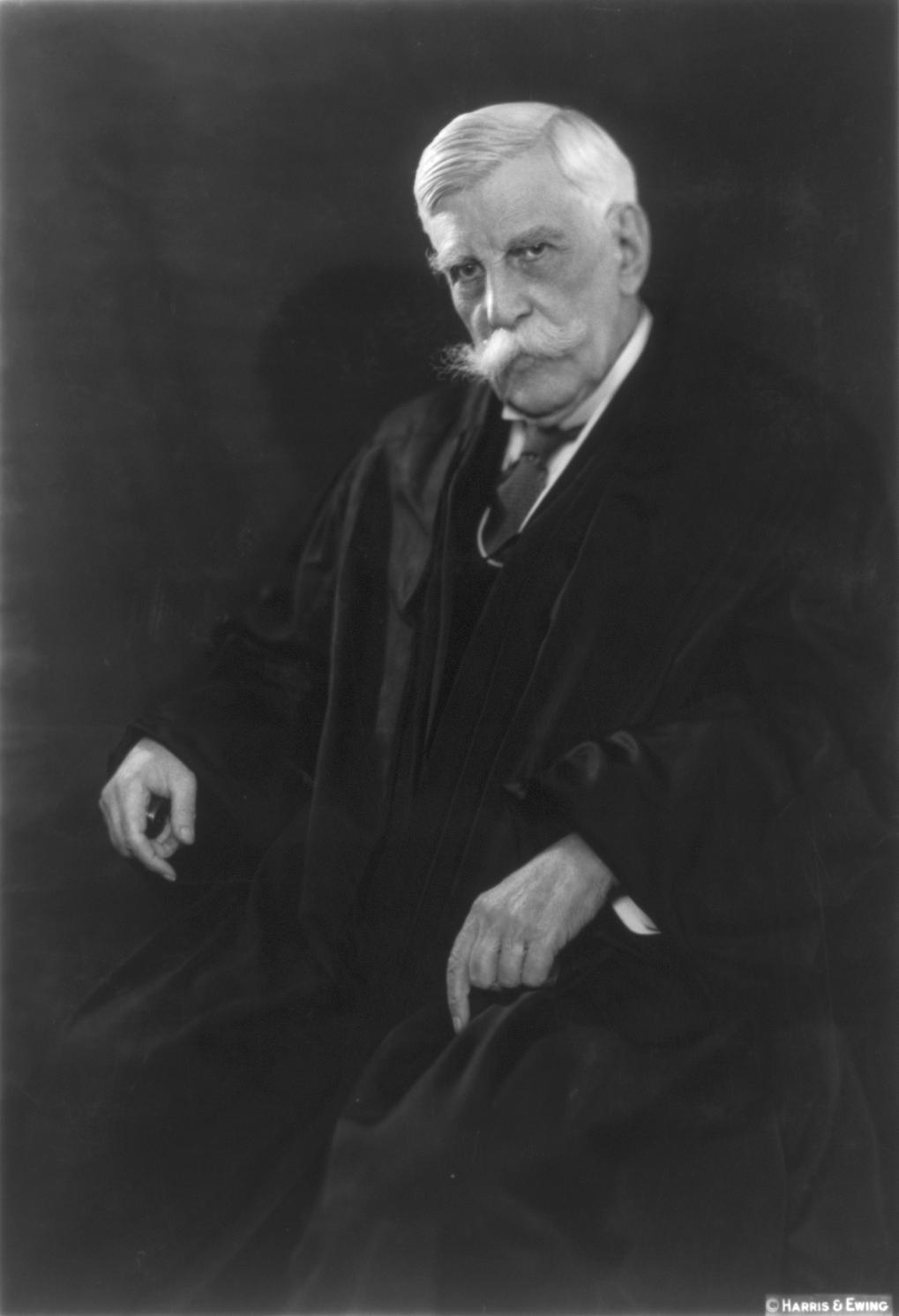

The net effect is a state tax deduction is created with a little preplanning and simply moving assets around the country; at least this is the way the state's want to portray the strategy. Tax planners and corporate tax directors call this smart corporate tax strategy. Of course, the subsidiary that holds the trademarks and trade names (and other corporate secrets) does a lot more than just hold intellectual property. These assets have t o be actively managed and protected. As any "IP Attorney" will tell you, the realm of intellectual property law is complex and ever changing. Think about it, who wouldn't actively protect their company's most valuable property? Furthermore, as the honorable Judge Learned Hand is often quoted saying:

o be actively managed and protected. As any "IP Attorney" will tell you, the realm of intellectual property law is complex and ever changing. Think about it, who wouldn't actively protect their company's most valuable property? Furthermore, as the honorable Judge Learned Hand is often quoted saying:

Anyone may so arrange his affairs that taxes shall be as low as possible; he is not bound to choose a pattern which will best pay the Treasury; there isn't even a patriotic duty to increase one's taxes.

Having explored the concept of trademark planning from 30,000 feet and sidestepping the argument of whether trademark planning is just or improper, let's turn our attention to the state's methods of dealing with the trademark planning strategy. As mentioned at the start of this article, the trademark planning strategies have been utilized by corporate tax departments for decades - and the state's have been fighting the concept for almost as many years. The question most often turns on whether the state can assert jurisdiction over the trademark planning company when it has no employees, no physical assets, and not other contact with the state other than licensing intangibles into the state.

In my example, I used Toys R Us as our hypothetical company because the company was involved in one of the most famous trademark planning cases to date - Geoffrey (the name of the famous giraffe owned by Toys R US) was the name of the trademark planning company created by Toys R US in the 1980's. South Carolina successfully asserted that the licensing of intangibles created substantial nexus, which is constitutional jargon for enough contact with the state for the state to assert jurisdiction over the company without violating US Constitutional limitations, naming the Commerce Clause. Since this case, several states have followed South Carolina's lead with economic nexus, while other state courts have refused to find nexus in almost identical circumstances. Other companies such as Sherman Williams and Barnes & Noble have faced state challenges of their trademark planning companies in various states as well. This brings us to the Circle K case in Florida.

Circle K utilized a very similar strategy of trademark planning as Toys R US, utilizing an out of state subsidiary to managing the corporate intellectual property for the conglomerate of subsidiaries owned by the company. Florida decided that this was a good case to challenge the practice and asserted nexus over the out of state trademark planning company. Circle K followed all the administrative appeals process, which the Florida Department of Revenue summarily denied. So Circle K sued, knowing as you are about to that it had a ace up it's sleeve. Even if a Florida was successful in asserting nexus over the out of state company, there is a quirk in Florida's method of calculating taxable income in Florida that would prevent the out of state trademark holding company from owing any Florida Corporate income tax.

Without going into too much detail, when a state taxes a company operating in multiple states, the state can only tax the state's fair share of the company's income. This makes sense; otherwise every state would try to tax all of a company's income. (Could you imagine 30 states imposing a 5% corporate income tax, which would equal 150% overall state tax rate.) So the states are constitutionally required to "fairly apportion" a company's income among the states. The most accepted formula for apportioning income among the states is to look at the company's property, payroll, and sales in the state versus the company's property, payroll, and sales everywhere. This rudimentary formula creates a percentage that is multiplied times the company's overall taxable income to determine how much of the company's income can be taxed by the state. Florida also utilizes this formula, but there is a catch in determining what is included in the 'sales' factor of this formula.

Under section 220.15, Florida Statutes, the only income from royalties allowed to be included in the numerator or denominator of the sales factor are royalties from minerals and mining operations. Because the out of state Circle K subsidiary does not have any property or payroll in the state and by a clear and plain reading of Florida's apportionment statutes, there are no sales that can be included in the sales factor, the apportionment factor for ANY trademark company in Florida is zero. This results in zero taxable income in Florida for a properly executed trademark planning company. Very shortly after Circle K made this argument in front of the judge, the state of Florida settled the case out of court before creating a judicial precedent in addition to the very damning apportionment statute. So, as the title to this article implies, trademark planning is still a viable strategy in Florida.

Please note, there are other means of attack utilized by other states that Florida could create statutorily to battle these tax planning strategies. For example, some states have stopped trying to go after the out of state trademark planning subsidiary. The state already has jurisdiction over the in state subsidiaries taking the tax deductions for royalty fees. These states simply created statutes denying deductions for royalty fees paid to affiliated companies, also known as "add-back statutes." There is only one strategy that I can think of to challenge an add-back statute, which is to outsource the trademark management function to an unaffiliated subsidiary so the add-back statute would no longer apply. Other states, such as California, have gone too much greater lengths by forcing most related companies to file one combined return, eliminating all intercompany transactions, including the royalty deduction.

If you have any questions about this case or trademark planning in general, then please do not hesitate to contact our firm for a free initial consultation by phone or email (available at the top of this web page).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: MR. SUTTON IS A FLORIDA LICENSED CPA AND ATTORNEY AND  A SHAREHOLDER IN THE LAW FIRM the Law Offices of Moffa, Sutton, & Donnini, P.A. MR. SUTTON IS IN CHARGE OF THE TAMPA OFFICE FOR THE FIRM AND HIS PRIMARY PRACTICE IS FLORIDA SALES AND USE TAX CONTROVERSY. MR. SUTTON WORKED FOR THE STATE AND LOCAL TAX DEPARTMENT OF A BIG FIVE ACCOUNTING FIRM FOR A NUMBER OF YEARS AND HAS BEEN AN ADJUNCT PROFESSOR OF LAW AT STETSON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF LAW SINCE 2002 TEACHING STATE AND LOCAL TAX, ACCOUNTING FOR LAWYERS, AND FEDERAL INCOME TAX I. YOU CAN READ MORE ABOUT MR. SUTTON IN HIS FIRM BIO.

A SHAREHOLDER IN THE LAW FIRM the Law Offices of Moffa, Sutton, & Donnini, P.A. MR. SUTTON IS IN CHARGE OF THE TAMPA OFFICE FOR THE FIRM AND HIS PRIMARY PRACTICE IS FLORIDA SALES AND USE TAX CONTROVERSY. MR. SUTTON WORKED FOR THE STATE AND LOCAL TAX DEPARTMENT OF A BIG FIVE ACCOUNTING FIRM FOR A NUMBER OF YEARS AND HAS BEEN AN ADJUNCT PROFESSOR OF LAW AT STETSON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF LAW SINCE 2002 TEACHING STATE AND LOCAL TAX, ACCOUNTING FOR LAWYERS, AND FEDERAL INCOME TAX I. YOU CAN READ MORE ABOUT MR. SUTTON IN HIS FIRM BIO.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

CIRCLE K ENTERPRISES INC vs FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE, Case No 2010 CA 1353 (Original Complaint)

CIRCLE K ENTERPRISES INC vs FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE, Case No 2010 CA 1353 (FL DOR's response)

© 2013 All rights reserved - James H Sutton Jr